- Home

- Amy Bonnaffons

The Regrets Page 2

The Regrets Read online

Page 2

I decided to experiment with form. First I tested the waters with a simple slide into self-parody: 8:15 a.m. produced small fart; medium-sized fart followed 8:17. Then I harnessed my attention to mental as well as physical events: 10:07 p.m. experienced twinge of nostalgia. 10:08 investigated source of nostalgia, discovered Proustian memory link between buzz of apt. overhead light and similar buzz of empty fluorescent-lit college classrooms which would enter after dark to read in relative silence. 10:09 prodded by nostalgia, picked up book of poetry, read phrase “black milk of daybreak,” realized how perfectly that phrase describes insomniac city sky—never entirely dark.

Finally, unavoidably, I went meta: Unsure how to break down increments of day. What constitutes increment? One hour? Fifteen minutes? A few seconds? Word “activities” seems misleading as well. Is not everything an activity, including the writing of this report? Should one include the writing of the report in the report? Or would such activity become self-defining, tautological, an Escher hand drawing itself?

No matter how many versions I wrote, though, my reports all felt inaccurate. My thoughts and emotions seemed suspicious, of dubious origin. I experienced them in the third person. Here was a guy who looked like me, living some kind of life, interacting with things: the newspapers, the bagels, even the nostalgia. I didn’t quite trust this guy. I overcompensated by paying extra-close attention, as if I could catch him in the act. Sometimes, I briefly inhabited the first person: for a jolt of surprise, or a brief saturation of pleasure. But then, inevitably, the past slammed up against the present, like somebody shouldering down a locked door: a rattle, a loosening, a rushing-in-of-darkness.

* * *

Structured activity is an excellent antidote to loose and dangerous thoughts. Enjoy the hobbies you practiced in your previous life—or try something new! Try to resist the temptation to tie your current “life” to your previous life. Remember: strictly speaking, you do not exist.

You do not exist. But I’d never felt my existence more sharply, the painful way you might feel the light in a room when it starts to flicker, when the bulb is just this side of burnout. Dozens of times a day, I started to fall out of myself and then snap, startled, back in. My existence buzzed and crackled. It was impossible to forget.

I tried to set up a routine. Each morning, I went to the coffee shop and sat there for several hours—mostly just looking around, observing the patrons as though they were zoo animals—marveling, as one does with zoo animals, at their exquisite self-absorption, their unstudied naturalness in their flimsy environment. I couldn’t believe I used to be one of them.

This café was a place I’d strenuously avoided, in my previous life. It’s called, simply, COFFEE, but the name isn’t displayed anywhere, except on the menus. The storefront is mute, just brick and frosted-glass windows through which, if you bother to stop and look, you can glimpse the low wobbly tables, the paisley wallpaper, the gleaming futuristic hulk of the espresso machine. I’d always found the place pretentious, especially its name (so anorexically smug) and the coy withholding of it (what did they think they were, anyway: a twenties speakeasy? Did they find advertising too gauche? Did they fear the clamor of the unwashed masses demanding their walnut and Gruyère panini, if only they knew?). But it was only half a block away, and its ludicrous machine happened to make electrifyingly good espresso, and despite being dead, I blended right in.

I even came to feel affection for the baristas there, all hipster caricatures: the tall, leonine South Asian woman in baggy pants and suspenders over a tight midriff-baring shirt; the redheaded trans guy with the nose piercing and the T-shirts advertising bands I wasn’t cool enough to know about (UGLY LITTLE DARLING, CHARLIE BROWN LOVES THE RADIO, VULVITUDE); the pale busty girl in the vintage dress and secretary glasses, a tattoo of a mermaid in a top hat spanning the length of her forearm.

I realized early on that this girl, mermaid tattoo, was actually someone I had met before. We’d once shared a joint at a roof party, sitting in a tight circle with a couple of other strangers. She kept calling me “Thomas Aquinas,” for no particular reason—some kind of perverse anti-flirtation, or meta-flirtation. I’d volleyed capably, sure of the rules if not of what the game meant: her name was Meg or Maggie, but I called her Saint Margaret all night. We parted amiably; before I ducked out of the party, she grabbed my arm to hold me in place, then solemnly made the sign of the cross.

The first day I came in, I saw Saint Margaret at the helm of the espresso machine and froze. I nearly turned around and walked out. But the other barista, the trans guy, had already noticed me, was looking up in sullen expectation, waiting to take my order; I felt weirdly paralyzed, unable to break the social code and about-face.

As I stumbled through my order, my eye on Saint Margaret, I remembered the memo’s words: You may be wondering how you’ll possibly remain unnoticed, in the landscape of your former intimates and acquaintances. It may seem odd to you that we’ve provided you with no disguise.

Death itself is your disguise. No one is expecting to see you—so they won’t. When Jesus appeared to Mary Magdalene, she thought he was a gardener.

When I left the café, usually around nine thirty, I’d catch the bus to the mailbox to mail the previous day’s report. By the time I returned to my neighborhood, I was exhausted; I’d rest for an hour or two, then find some way or another to whittle away the remaining hours—walking, reading, attempting to paint—before I could officially declare the day “finished,” and begin my description of it in the next report.

On one of my very first days I’d gone to the art supply store, gotten a canvas and brushes and palette paper and a few tubes of color. In the past, this—painting—was what had always worked most reliably to get me out of myself. It had nothing to do with “expressing” anything. It was pure displacement, the same objective I might have accomplished through tennis or gardening or the fussy concoction of a flawless ceviche, with lots of fresh-picked herbs and tiny knives. The drama of thwarted will, of attempted sublimation: eventually achieved, temporarily, like a pulse of open sky through the brain.

I’d dropped out of art school after one semester, when I’d realized that it was no different from business school: a backdrop for parties and starfucking, a generator of jargon. If that sounds snobby and self-righteous, well, I am a self-righteous snob about some things, but in this case I actually envied people like my classmates (Therese among them): their desire to share their work was fierce enough to withstand all the coarsening influences of the art world—the buffeting of the ego, the corrosion of exposure. I lacked that kind of faith. I feared that if my art ever made a name for me, that “name” would only smother me beneath the weight of myself; the whole point had always been disappearance.

I quit, and took a job managing the office of a small design firm. I enjoyed the role. It fit me—and strategically obscured me—like a uniform. I painted and played music when I felt like it. And I assisted Therese when she started to take off as a photographer, to rack up clients and commissions.

This pleased me: she’d always been the real artist between the two of us anyway. When we set up shots together, it was she who had the terrifyingly precise instinct for the placement of an object or the angle of the lens; she who could anticipate, almost prophetically, the moment when the light would shift from cottony vagueness into spectral purity; she who understood the language of objects, their relational syntax, the web of meaning that could arise in the specific distance between a blue clay bowl and a saltshaker and be annihilated, or rendered cliché, if the saltshaker is moved half an inch too far to the left. After all our years together, she was exquisitely legible to me. In every furrow of her brow, every half-articulate direction, I read exactly what she intended, and executed it perfectly. I was happy to abdicate agency, to mute myself in service of whatever it was that moved with such authority through her. I felt like the manservant of a shaman, or the solemn, scurrying altar boy anxiously reading the gestures of an abstract

ed priest. After working with her I always went home and did my best painting; I was hollowed out and humming, I got to coast on the current we’d set in motion together, and at those times I had a feeling of wordless well-being that I can recognize, in retrospect, as gratitude.

But now, when I sat in front of the canvas in my tiny room, I experienced something like a panic attack: my heart started to pound, and I felt a thickening in my chest, and I had to put all of my effort into simply steadying my breathing. I tried to trick myself into painting; I covered the canvas in a light pink primer and then added a few slashes of blue, something deliberately abstract, and told myself, See? You can do it. What I meant was, you can paint something that has nothing to do with any of this; you can use this brush to take you out of yourself. But then one of the lines started to curve slightly so that it resembled her arched eyebrow, and I was gasping like a hooked fish, and I realized that no matter what I did, there was only one image in my head, Dopplering around like a siren, even in its departure always about to return.

* * *

Therese and I had been inseparable since childhood, when we’d lived in identical split-level ranch houses next door to each other in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, divided only by a low hedge. Both only children, we were drawn together by mutual structural loneliness, though our families couldn’t have been more different. Mine were natives of the high-haired Cracker Barrel South, thrice-weekly attendees of the Church of Christ the Redeemer, owners of a house full of ceramic angels and throw pillows needlepointed with Bible verses.

They were also hopeless falling-down drunks. They managed to partially conceal this fact, thanks largely to the bright-faced denial of their church friends but mostly to my timely interventions. (I knew how to read the telltale weave in Andy’s step, the slight increase in the shrillness of April’s laughter; I grew expert at orchestrating excuses for us to leave public gatherings, including an alarming case of chronic Pretend Asthma. More than once I had to drive us home, my feet barely reaching the pedals.)

Therese’s parents, on the other hand, were atheists and foreigners, scientists at the Oak Ridge labs; Adele was Algerian by way of Paris, Tim a Jew from New Jersey. In New York they would have blended in perfectly, but in de facto segregated East Tennessee—well, Therese was the only even partially black kid in our entire school who did not come from the neighborhood that lay, literally, on the other side of the train tracks. I’m sure my parents would have objected to my association with the Golds—officially on account of their godlessness, not their race—except that I had no other friends.

Tim and Adele subscribed to The New Yorker and Scientific American and treated their daughter as a near intellectual equal, including her in their discussions of Modigliani or the oil crisis, regarding our play with distant amusement. Their house’s interior was the opposite of ours: sparsely furnished, with a few uncomfortable thrift store chairs, some lazily framed modern art pieces, not a single doily or cut-glass Jesus figurine. Yet I always felt completely at ease there, able to relax, temporarily released from the strain of my eternal vigilance.

Tim let us borrow the expensive Leica he had toyed with in grad school; Adele took us to museums. It was in their house that I experienced other essential rites too: it was there I tried my first espresso, sampled unpasteurized cheese, and even, finally, lost my virginity, not without strenuous effort, high-fiving Therese against her headboard when it finally took, while Tim and Adele indifferently watched PBS downstairs. This was during the period, in high school, when we made a brief earnest stab at couplehood, encouraged by the fact that everyone already thought we were a couple anyway, undeterred by our baffling lack of desire for each other.

Once we’d achieved the trophy of virginity loss, we went our separate ways sexually; Therese went to Smith and discovered the personal and political advantages of pursuing pussy, while I entered a series of short-lived, fuse-blowing affairs with dark-haired women, mostly older (professors, bosses, aimless single moms who frequented the bars I tended). If Therese and I occasionally and half-heartedly pawed at each other when we found ourselves single and bored, I was mostly to blame for that. I was mostly to blame for most things.

* * *

When we were nine years old, when we’d been inseparable for nearly a year, Therese’s family went away for three weeks, to see Adele’s relatives in Paris and Algiers. Three weeks to a Tennessee kid during the summer—especially a Tennessee kid with exactly one friend—is an eternity: the yawning emptiness of the unstructured hours; the sun sliding slowly down the day, like an egg yolk on the inside of a glass; the ominous drone of cicadas buzzing outside the window. Your blood grows sluggish, your mind feels dead. It was on one of these endless afternoons, while I read a comic book on the floor of my bedroom, that the angel appeared.

There was no blast of trumpets, no grand entrance; I simply noticed that a shadow had fallen over my book, and then I looked up and saw her there. She was sitting on my bed, serene and composed in her white draped gown, her huge feathered wings spread out behind her, spanning the width of the room. One of her wings lightly grazed the tops of my Bible camp trophies, sending a swirl of dust dancing into the air. She was blindingly beautiful, bright against my faded red comforter and the musty, muted yellow light of the bedroom.

“Come here, Billy, sweetheart,” she said, holding out her arms. “Come here and sit on my lap.”

My mouth fell open in protest—my name, of course, was not Billy—but nothing came out.

“Don’t be afraid,” she said, beckoning with both hands. “I just want to give you a hug.”

I stood up and shyly approached her. Her long glowing arms closed around me, drew me onto her lap.

How do I describe the feeling of being held by an angel? Imagine the most transcendent, God-soaked music you’ve ever heard, then imagine yourself inside that music, imagine yourself being that music. Or think of the best orgasm you’ve ever had and imagine that it’s taking place not just below your waist but in every cell of your body, all four chambers of your heart, even your eyelashes, even your fingernails. Imagine heroin, if it helps; I hear that’s pretty great. Anyhow, imagine this: everything gone except pure pleasure, utter wholeness.

My body felt weightless, suffused with light. I was dimly aware that the feeling had edges—that somewhere beyond it lay my jagged nighttime terrors, my only-child solitude, the anxious responsibility I felt for my parents, for the world. But this new feeling begged the question: what was the world, anyway? The world began and ended in the cradle of this body. All the old darknesses seemed trivial—distant and silly, little pencil smudges at the edges of eternity.

“There, there, Billy,” said the angel. She gently released me, then reached back into the folds of her left wing and produced something. She held it out. “Take this and swallow it,” she said. The object was a small black stone.

I no longer cared that my name wasn’t Billy. I didn’t care whether any of this was meant for me. When you’ve just been gifted the greatest pleasure of your life, you don’t look it in the mouth. You don’t consider whether or not you deserve it. You only want more.

I didn’t hesitate. I took the stone, slipped it into my mouth, pushed it around with my tongue for a second—it tasted silty, like lake water, but also sweet—and then swallowed it. I felt it go down my esophagus, carving out a dark passage through my light-filled body. I was briefly seized by an uneasy premonitory twinge—but then the angel drew me to her breast again, and it instantly dissolved.

A few seconds passed. Then she leaned back, held me by the shoulders, frowned into my face. “Nothing’s happening,” she said.

I felt a dark, scribbly panic. “What’s supposed to happen?” I asked.

She didn’t respond. Instead, she frowned deeper and drew me in close again. But her embrace felt different now, anxious and clutchy. My panic churned and deepened. “What’s wrong?” I asked, my voice muffled by her breast.

She held me again at arm’s length, nar

rowed her eyes. “Open your mouth,” she said.

I did. “Wider,” she said. She inspected my mouth like a dentist, sliding her finger along the roof of my mouth and under my tongue. Then she leaned back.

“You’re sure you swallowed the stone?” she asked.

I nodded.

She let go of me, looked distractedly out the window. “Well,” she said. “Well, fuck.”

I gasped. In our house, to say that word was tantamount to committing murder. In fact, I had never heard it spoken aloud by an adult. For the first time, it occurred to me to distrust what was happening.

The angel turned back to me. “You’re not Billy,” she said. “Are you?”

I shook my head, my eyes filling up with tears.

“Fuck, fuck.” She clutched her lovely head, turning it from side to side. “Excuse my language. I have to go. I don’t have a lot of time to fix this.”

“Are you coming back?”

She didn’t answer. “Be a good boy,” she said. “Okay?” She mussed my hair distractedly, and then she was gone.

Just like that. One minute I was perched on her heavenly lap; the next, there was nothing beneath me but air. My balance thrown, I tumbled gracelessly off the bed and clunked onto the floor, slamming my elbow against the wooden bedpost as I fell.

“Ow,” I said. In the now-empty room, my voice sounded small, a petty little-boy whine. I looked around. The room appeared exactly as it had before: the twin bed with its faded comforter, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle wallpaper, the dark blue shag rug, my X-Men comic splayed out to the page I’d just finished. Yet I could still feel the black stone churning around inside me, as final as the period at the end of a sentence. I got up, went to the bathroom, stood over the toilet, and tried to retch it up. Nothing came up but air.

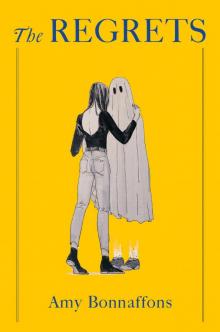

The Regrets

The Regrets