- Home

- Amy Bonnaffons

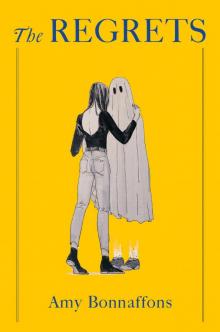

The Regrets

The Regrets Read online

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright © 2020 by Amy Bonnaffons

Cover design by Julianna Lee

Cover illustration by Mio Im

Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

Twitter.com/littlebrown

Facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: February 2020

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Boots image [here] by Brittainy Lauback

ISBN 978-0-316-51614-3

E3-20200107-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20200103-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20200102-DA-NF-ORI

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Thomas

Rachel

Mark

Thomas

Mark

Rachel

Acknowledgments

Discover More

About the Author

Also by Amy Bonnaffons

For everyone stuck between this world and another;

for anyone who struggles to stay here

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

Mortal, your life will say,

As if tasting something delicious, as if in envy.

Your immortal life will say this, as it is leaving.

—Jane Hirshfield

I have scars on my hands from touching certain people.

—J. D. Salinger

Thomas

* * *

You may relive—vividly, and at unexpected times—the moments preceding your death. This symptom is natural in those with no Exit Narrative. Refrain from seeking any form of self-medication (pharmaceutical, alcoholic, sexual, or otherwise), or you may incur regrets.

It’s true what they say, that things slow down. Of course it’s terrifying—but also beautifully seamless, as if choreographed. I see my death coming, the way you see a fly ball arcing toward your spot deep in the outfield. It is round and perfect. It has the exact right shape and heft. It comes straight for me as if magnetized.

Then: nothing. I remember that seamlessness, the feeling of it, but I can’t reconstruct it. Trying to grasp the moment itself is like clutching a fistful of broken glass. It cuts me open. I fall out of myself.

* * *

I remember what happened right after. I heard the first siren, and then the angel appeared above me: a gash of light resolving into the shape of a woman, with large feathered wings beating bright against the darkness.

The sight stunned me into silence, and I realized I’d been screaming. Now the world was still, and I was the center—pinned in place by the angel’s gaze. She hovered above me for a moment, then descended to embrace me.

Now her soft chest was against my chest, her warm thighs wrapped around mine, the skin of her cheek against my own—if she could even be said to have skin; it felt more like concentrated light, warm and surfaceless. My body rose like a plant stretching sunward. The rough asphalt still pressed up against my raw back where my clothes had been torn away. I could still feel the gravel in my wounds, the pressure of a wrongly angled bone against the ground. I could still sense the presence of Therese’s body, somewhere to my right, like a part of my own body that had been cut away. But as the angel held me, my pain drained like bathwater, replaced by something sweet and liquid—like honey, or melted gold. I heard myself moan with relief.

The angel brought her face within an inch of mine; we breathed each other’s breath, like lovers. “Swallow this,” she said. Then she placed a small black stone on my tongue. Simultaneously, she slid her other hand between my legs. I gasped, and my cock grew hard as bone.

I knew what was happening, and I was not afraid. I’d been waiting seventeen years for this exact moment.

But the next thing I knew, I was choking, and the black stone was flying out of my mouth, and my body was reeling away from the angel’s as though she’d struck me: my skin shrunk back and my cock curled in, limp and useless. My body had rejected the gift.

The angel peeled herself off and hovered above me, her wings beating lightly. I could tell by the expression on her face—frightened, then clouded with doubt, then clearing in sudden recognition—that she knew what was happening. She folded her arms.

“We’ve met before,” she said. “Haven’t we.”

* * *

The Officer sat across from me, behind a bulky desk made of cheap-looking wood—or more likely imitation wood, its grainy patterns suspiciously intricate, its surface giving off a dull matte half sheen. Behind him, two dusty venetian-blinded windows admitted no light at all. Twin phalanxes of green metal file cabinets bracketed the walls on either side of the desk. The walls themselves were made of a porous cream-colored cinder block, like petrified tofu. A brittle, curly-edged Civil War battle sites calendar was turned to MAY: APPOMATTOX. A yellowish-brown water stain, shaped like a cockroach, spread across the flaking plaster ceiling.

“So. Thomas Barrett,” said the Officer. “Can you describe, in detail, what just happened?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Can I ask a question first?”

He made a go-ahead gesture.

“Why do I feel like I’m in my elementary school principal’s office?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“This room looks exactly like Mr. Antonucci’s office. My elementary school principal. Not that I’ve thought about it much since my last visit there, but it’s uncanny. The color of the walls, the water stain. Even the Civil War calendar. He had one of those.” I took in a breath. “Are you Mr. Antonucci?”

He shook his head tightly. “What is happening is that you are mentally enacting your conception of authority.”

“Doing what? You mean I’m imagining this?”

“Your mental conceptions are shaping your visual perceptions. But I exist, just as strongly as you do.”

He was not a large man; he wore a cheap suit, dandruff-flaked and tight at the shoulders. But none of this detracted from his dignity. His high bald brow was stately and imposing. He did look a bit like Mr. Antonucci, though not exactly: it was a loose translation. They could have been brothers. But the eyes were identical—dark brown, penetrating, hooded like an eagle’s.

“So,” I said. “You’re larger than life. You’ve got impressive eyes and shoulders. But your furniture’s so shitty.”

“Excuse me?”

“I’m just observing. I mean, if this is my conception of authority, that’s fascinating. It’s like part of me respects you and part of

me views you with contempt. Or despair.”

“That’s possible.” He nodded. “But let’s not get distracted by speculation.”

“Sorry. What was your question again?”

“What do you remember,” he asked, “of what just happened? Of what brought you here?”

Something about the combination of words he’d used—the word “remember” and the word “here,” perhaps—set off a full-body tremor, or more like a full-body flinch. I found myself contracting, like one of those roly-poly insects that tightens into a ball when you graze its exoskeleton with your finger: folded up, with my head between my knees, breathing quickly and shallowly, protecting myself against what felt like an onrush of unwelcome light.

“Yes,” said the Officer. “It’s as I assumed.”

“It’s how?” I asked, managing—slowly—to unwind myself, to sit up straight again, to deepen my breathing.

“You’re insufficiently dead,” he said.

“I’m what?”

“Insufficiently dead. You lack rupture with your life. You have no exit narrative.”

“Exit narrative?”

“Look,” he said, standing up and pushing his chair under the desk; it made a rusty creaking noise as it scraped against the linoleum floor. “This is difficult to explain, but what you should know is that we take full responsibility. They’re extremely rare, but these institutional errors do happen from time to time. I’m referring to April eighth, 1996, when you were nine years old. To what happened with Nineteen. It’s a scenario we refer to as ‘early exposure.’”

“Wait—her name is a number?”

“She will receive the appropriate discipline, of course. You know, she got unlucky: if you’d been assigned a different Agent this time, you’d never have been able to identify her. That’s what she was counting on. But it happened this way, so she confessed to the mistake—which is why you’re here.”

“So, then…what now?”

“Well,” he sighed. “I believe that, in the end, you’ll be glad for this opportunity. Most people don’t get the chance to experience the state you’re about to experience. In any event, it’s highly educational.”

“Wait a minute. Where’s Therese?”

“Your friend? She had a narrative.”

“What was her narrative? Where is she?”

“Don’t get agitated, please.”

I stood up. “Where is she?”

“Have a seat.”

I sat down.

“I’m on your side, Thomas,” he said. “I can’t change the rules. All I can do is explain them to you.”

“So, what are the rules?”

He slid a stapled document across the table, brittle and yellowed at the edges, in an antiquated font, as if it had been printed sometime in the mideighties and languished in a file cabinet ever since.

Please adhere to the following guidelines during the period of your re-manifestation. Everything about these guidelines, including their stringency, has been carefully designed to prevent regrets.

I looked up at the Officer. “What do you mean by regrets?” I asked.

“Regrets,” he said in an announcer’s formal tone of voice, as though reciting a definition. “Incursions of the past into the present. Threats to one’s temporal integrity. An inability to coexist with oneself.”

This hardly cleared things up, but I let it go. “What about Therese?”

He shook his head slowly, implying No to more than just the question I’d asked. With a throb of dread, I began to understand.

* * *

When I first awoke, after my visit to the Office—but no, “awoke” is the wrong word, because I hadn’t been asleep; I had been somewhere else, or perhaps something else—in any case, when I suddenly found myself supine on the narrow twin bed in that small cold apartment, staring up at the cracked, stained ceiling, I didn’t know, or remember, that I was dead. Nor that I’d ever been alive. I’d been wiped utterly clean. I was nothing and no one—a blinking cursor on a bright blank page.

For a period of time that could have been moments, or minutes, or hours, I existed like this, like a held breath. No, not exactly held, which implies a certain intention, a feeling of suspense. This was more like the space between breaths: at the crest of an inhale, right before it becomes an exhale. Precisely the space (I remember now, from the few sessions of meditation class I once attended) that the Buddhists point to as evidence of “nonself”: what is the breath, can the breath be said to exist, when it is neither inhalation nor exhalation? By extension, can one’s identity as a distinct and separable self be said to exist, in its similar state of perpetual change and becoming, never exactly one thing nor another?

I am trying to conjure this feeling in all its specificity because I feel a terrible nostalgia for it; I wish it would return. Because what eventually punctured this peaceful blankness was a sudden and massive surge of grief.

I still didn’t remember what had happened; the feeling had no referent. I just knew that I had lost something, or everything—that I had lost. The grief rammed through me, tearing a jagged, ugly, guttural noise out of my body. Then I began to remember.

First I remembered the angel straddling me there on the asphalt. Then, piece by piece, other images began to return. I couldn’t yet stitch them together—and yet on some bodily level I began to perceive the connection between them. The connection was me. I was a me, an I, a person.

Eventually, as this fact sunk in, my shudders began to subside. I found myself able to sit up straight, to take in my surroundings: a small room, perhaps eight feet by ten, furnished sparsely with a twin bed, a small metal desk and rickety folding chair, and a meager kitchenette (mini fridge, hot plate, sink). Through one door, partly opened, I glimpsed a bathroom; another door, now shut, presumably led to the outside world. The room’s only other opening was a small window above the bed, its smudged glass guarded by vertical iron bars. On the small desk lay a crisp stack of twenty-dollar bills and a printed memo: ATTN: THOMAS BARRETT (REFERENCE #1037).

Something snapped into place, like a lock sliding home: recognition, tinged with dread. That’s me, said a voice in my head. That’s my name—Thomas Barrett.

I had not chosen to come back. I’d been tugged back into this world against my will, by the thread of my own name: yanked from a cool blank nothingness into a web of cause and effect. Like it or not, my story was still happening; like it or not, I would have to write its ending.

* * *

You have been sent back to a place very close to the home you recently vacated, in a body that exactly resembles the one you left behind. Your return was necessary due to an institutional error, for which we sincerely apologize. These errors are rare, but they do occur. Errors include Mistaken Date of Death (error code 2578), in which the subject is delivered to the Processing Center too early or too late; Mistaken Identity (error code 1049), in which the wrong subject is delivered to the Center; and, much more rarely, Early Exposure (error code 3627), in which the subject encounters one of our Agents earlier in life and thus finds him- or herself unable, at the moment of final Consummation, to experience the potent mixture of shock, desire, terror, and awe necessary for catharsis and closure.

The period of your stay will be approximately three months. This window allows us to complete the procedures necessary to process your eventual arrival. When we are ready for you, you will receive a written communication from us, detailing instructions for how to return to the Office.

The rest of this document outlines several important rules for the period of your re-manifestation. To be clear: we have no means of enforcing these rules, which exist for your benefit only. We can only warn you that, should you ignore them, you are almost certain to incur regrets.

* * *

The body you have been granted, while identical in most ways to the body you vacated, is nevertheless provisional and loosely structured. You may experience feelings of dissociation; numbness to sensation; excessive sensation

; burning, freezing, or floating; and a loss of the ability to distinguish between mental, emotional, and physical realities.

For weeks after my return I could barely sleep, like a nervous hummingbird. I’d catch an hour or two and then snap awake, heart pounding, with the panicked feeling that I was in the wrong place. Then I’d look around the room, with its bare water-stained walls and Spartan dorm room furniture, and I’d remember where I was, and why.

By the time gray predawn light began to stream through the curtainless window, any further sleep was a lost cause. I’d get up, splash some water on my face, and go downstairs to sit on my stoop until the coffee shop opened.

This turned out to be my favorite time of day: its coolness, its silence. The city looked scrubbed and expectant; the block crouched, hushed, like a tree just moments before all the birds launch themselves from its branches in one rustling swoop. In the morning my pain was mostly just the ache of being in the world, enfleshed and aware; I’d sit there on the stoop, opening and closing my eyes, gently trying to assimilate the unbelievable fact of this body.

* * *

You are responsible for daily reports of your activities during the period of your re-manifestation. These reports allow us to monitor your whereabouts. Mail your report at the same time each day, from the location specified on the attached map. In your report, break each day down into discrete increments of time and report on your activities during each increment.

At first I took the task seriously. I broke down the day into increments, as directed: 8:45 breakfast (everything bagel, scallion cream cheese). 9:00–10:00 read New York Times (Metropolitan, Week in Review). 10:00–11:00 rode bus to mailbox, mailed previous day’s report. But after a week or two of dispatching these missives into the void and wondering whether they’d even be read by anyone—or just deposited in some ancient file cabinet—the whole exercise started to depress me.

The Regrets

The Regrets