- Home

- Amy Bonnaffons

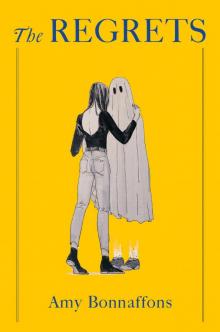

The Regrets Page 5

The Regrets Read online

Page 5

In my defense: I barely existed.

The girl with the red lipstick, or the idea of the girl, was a bright vivid gash through my loneliness: the hideous loneliness of the dead, a loneliness I can only describe as both infinite and suffocating, like a loop of musty bandage, layer upon layer of it, tightening as it thickens, deadening as it pains.

In my defense: is there a form of love that’s not a welcome unraveling?

Rachel

* * *

I first noticed him at the bus stop one hot day in mid-August. He was hard not to notice. I’m not the kind of person to use the word “aura,” but this man seemed to glow. Maybe it was a trick of his coloring: white-gold skin, golden-blond hair, green eyes that actually seemed to crackle electrically in certain lights. Even so, he looked distinctly sad, hunched forward on the bench with his elbows on his knees, staring off into space. Or perhaps into the dry cleaner’s across the street—it was impossible to be certain.

When the bus came, I got on, but he remained sitting there. I continued watching him while the bus pulled away. He didn’t move, but he seemed to somehow shimmer in place, rippling in the heat, like an optical illusion or mirage; by the time the bus rounded the corner I wondered if he’d been there at all.

But he was there again the next morning, and the next. He became a regular, always there when I arrived at the bus stop at eight forty-five. We took different buses. Usually mine came first, and I’d watch him as I left. In this way he came to seem like a permanent fixture of the bus stop, as though he lived there.

He dressed stylishly, in the same exact clothes every day: close-fitting jeans, striped boatneck T-shirt. He always carried a brown blazer with him, as though it might get cool, but I never saw him put it on.

There were many similarly stylish young men in my neighborhood. But these stylish men were never alone and almost never sad, at least in public. They’d saunter in and out of stylish restaurants, their stylish blade-thin girlfriends glinting beside them like swords at their hips. But this man always sat hunched and alone, looking both mournful and restless, his right knee bouncing up and down, staring out at the street with a last-chance look as if he’d be tested on it later.

I looked at him a lot. I touched him all over with the fingers of my eyes. Some men’s handsomeness is a trick of the light and cannot survive such probing, but he held up. His handsomeness was not detachable from him. It moved when he moved. It had sinew and pulse.

Sometimes he looked at me too, but then looked right away, back at the street, as if he had no time to be distracted—as if he had more urgent things to do with his electric eyes. To which I thought, Well, fine.

I work at a library. Not a fancy university library, and not one of the large venerable city libraries with marble steps or grand lobbies or statues of lions guarding the door. My library is a squat, shabby brick building on a side street in a quiet outer borough neighborhood. Our main patrons are elderly people who use the elderly computers to check their elderly AOL accounts, or who stop by to read the newspaper in Polish and then shuffle out with disgruntled looks on their faces, taking zero books. There are some toddlers during the day whose parents and nannies leave piles of sticky picture books on the Reading Together Carpet for us to clean up, and every day at around three, schoolchildren storm in and occupy the place for a few hours, loitering loudly, sitting at the large splintery wood tables to “do homework,” which really means finding excuses to giggle and poke each other with fingers and pencils under their shirts, testing their newly pubescent bodies as if for doneness.

Technically, I am the reference librarian, but very few of our patrons require me for reference. I spend a lot of my time straightening things up and alphabetizing. I love alphabetizing. I live for the lulls when I can travel slowly around the shelves, straightening spines, re-ordering titles. There is something so soothing in this, some inner rocking that happens when I move through the books, not conscious of their content but just of their physicality, their presence in the world as containers of words organized into patterns. I touch them one by one, and one by one they are there.

Only two other people work at the library: Jo-Ann and Tanya. Neither of them seems to care much about books. Jo-Ann mostly creates these terrible after-school events where she dresses up like Ms. Frizzle from the Magic School Bus and manipulates kids into making things out of construction paper. If you are a crazy person in New York there are many ways to shape your craziness so that its contours fit smoothly into the vessel of other people’s expectations. For example, most kids believe Jo-Ann is the literal Ms. Frizzle from the Magic School Bus just because she has red hair and wears elaborate earrings. They believe that if they make construction paper bookmarks according to her instructions, she just might take them to outer space or inside the human body. They always leave with this half-disappointed, half-relieved air that says, The world may be less magical than I’d thought. Tanya is from Jamaica and a mom of three teenage boys; she has permanent dark circles under her eyes and a good yelling voice. She is a genius with computers and can fix anything. She is also a genius at keeping the kids quiet and making sure that homeless people don’t leave needles in the restroom.

During lulls in my workday, I would sometimes close my eyes and think of the man from the bus stop, imagine what it might feel like for those electric eyes to linger on my face and body. I didn’t picture him touching me, just looking at me. Would some chemical reaction occur on the surface of my skin and work its way in, communicate something silent and profound?

I hadn’t had any kind of romantic relationship in almost a year. In New York, dating felt like public transportation during rush hour: brief spurts of headlong rushing energy, then long periods of waiting uncomfortably, bracing oneself against a series of casual violations.

The last guy I’d gone on an actual date with was a Buddhist. He’d just gotten back from Thailand, where he’d meditated in a cave, or perhaps on top of a mountain, one or the other, for a month. Not by himself, there were other people there, but they weren’t allowed to talk. This seemed about right, that you couldn’t get enlightened while talking to other people. But now he was talking. He kept using the phrase “penetrated by silence.” I closed my eyes and imagined a bright, thrumming silence entering me like a penis, emitting these sort of white rays that muted my body’s nervous noise. It seemed as though that was all I’d ever wanted. To be penetrated by silence. But when I opened my eyes nothing had changed: he was still sitting there, talking.

Supposedly, according to scientists, women are the more talkative ones—the verbal parts of their brains are all lit up, as opposed to the lit-up math parts in men’s brains. I’ve found the opposite. The whole reason heterosexual men need women, besides heterosexual intercourse, is that they need someone to verbalize the world to. Or rather, in whose general direction to verbalize the world. It’s like the way cats need a doorstep on which to deposit dead birds. Many women enjoy this role, or pretend to, but not me. There is a voice inside me, which I suppose is my voice but which I hear as if it’s someone else’s, the voice that says the words in my head when I read. My relationship to this voice is so intimate, so perfect, that most other people’s voices feel like intrusions.

Which doesn’t mean I don’t get lonely.

The golden man’s electric buzz grew stronger and stronger inside my head and body. Now he was touching me, and the touches felt like electric shocks, in a good way, like a zap that stunned my body into wakefulness. Perhaps he had been struck by lightning once, and survived with the lightning somehow trapped in his body; perhaps being touched by him would resemble being struck by small doses of lightning, dying and waking up, dying and waking up, over and over and over again.

* * *

There is a danger to daydreaming. It’s not that the daydream bears too little relationship to reality. It’s the opposite: the daydream can create reality. It can become so powerful that it transforms the face of the world, then encounters its own ima

ge and falls in love with itself.

This is not what psychologists call “projection.” It is not a delusion of the brain. It is real as rocks, as teeth, as nerve endings. I have fallen in love with my own daydreams and then they have gone out into the world and returned to me embodied as men. When I eventually fell out of love with these men, it was not because I discovered some sort of factual error; it was not that the men themselves were realer than the daydream. It was the opposite: these men could not withstand the daydream’s reality. They were not strong enough. The daydream slid off of them and went to seek its own kind elsewhere, and I had to clear the space around myself for it to return.

I first learned this lesson with my college boyfriend, Mark. Mark was kind and nice-smelling and wanted to be a doctor; I liked the warm, crooked way he smiled at me, like a cowboy grandpa.

But it wasn’t enough. We dated for two years before I accepted the fact that the daydream had deserted him permanently. In truth it had gone almost as soon as we began seeing each other, but I held out hope that it would return. My hope lay in a kind of experiment, about sex. Mark was only the second person I had slept with, the first I had slept with repeatedly. I had a notion that the daydream lived in my body and that if he penetrated me in the proper way he could touch it, coax it out into the space between us, then step into it like a second skin. Mark was very game and strove to conjure every possible kind of orgasm, but in the end they were all the same. I mean they were typologically different but all daydreamless, purely physical in essence. I isolated the common denominator and concluded that my orgasms from Mark would never be different because they all came from him. When I cheated on him with my downstairs neighbor Kazim, to expand my data set, the results were mixed: the orgasms from Kazim were also daydreamless, but different enough to convince me that the daydream would probably return to me in a different form, with a different person, if it ever returned at all.

The unfortunate thing was that Mark never understood about the daydream. All he understood was that he had been betrayed and found wanting. I tried many times to explain, and he tried very hard to understand. Each time we failed, we both felt lonelier. The difference was that my loneliness eventually took on an odd beauty, like a pine tree on a bald mountain in an ink painting; it made me want to actually be alone. His loneliness was suffocating, a form of panic; it made him want to get married. In the end I decided to study abroad in England and ignore all of his emails, and that did the trick eventually. He started dating his lab partner, and we never spoke to each other again.

Now my daydream about the electric man from the bus stop was growing in force; the daydream seemed to have attached to him thoroughly. Soon it would either draw us together or some crisis would occur that would cause it to evaporate. To delay the latter possibility, I avoided talking to him for as long as I could. I tried other methods of managing desire, of keeping it alive while preventing it from growing too strong.

For one thing, I told Flor about him. Flor is not my best friend, but she is my chief enabler. She is married to the only man she’s ever slept with, the man she’s been with since the first day of college, and she enjoys romanticizing my sex life. She actually uses that phrase, “sex life,” as if I have multiple lives and one of them is just sex, sex, sex. “How’s your sex life?” she’ll ask me, leaning across the table and doing a little wiggle with her eyebrows. If there’s something to tell, I will tell her, and then sometimes I’ll say, “How’s your sex life?,” to which she always just shrugs and says, “I don’t have a sex life—I’m married,” even though I happen to know that she and Arthur have lots of sex: she is constantly getting UTIs. So what she means by “sex life,” I’ve concluded, is not actual sex but the aspects of it she has renounced: the danger, the randomness and stupidity, the excitement of an alien penis. I am skeptical of her nostalgia but receive a certain authorial pleasure from shaping my encounters with men into sleek narrative capsules for her enjoyment. She doesn’t understand about the daydream, but I have discovered I can coax it into a sharper existence by enlisting her in my schemes for approaching the men to whom I hope it will attach.

“So you haven’t even talked to him yet?” she asked.

We were having dinner near her office on Lexington, at our favorite Pakistani restaurant, a poorly lit hole-in-the-wall patronized exclusively by male taxi drivers and by us. We always sat at a corner table and talked frankly about gynecological matters while the men stared at Bollywood videos playing on a television mounted to the wall and pretended not to overhear us.

“Nope,” I said. “I’ve only done the leg thing.”

The leg thing is something I made up, which actually works. Try it sometime—you’ll see. What you do is, when you feel a man’s eyes on you, you uncross your legs and then recross them the other way. It is a simple trick but what it silently communicates is your sexual restlessness: it indicates the presence of an energy emanating from your general crotch area, which you can barely contain.

“Is it working?”

“Maybe, but he hasn’t talked to me yet.”

“Maybe he’s shy.”

“I don’t know. He seems depressed, maybe.”

“Hmm. Didn’t you say you were going to stop dating depressed guys?”

“I said that?”

“Yeah. After that guy, what was his name…the weed dealer?”

“Oh. Drew. I just meant because he kept losing his erection. But I never knew for sure if that was from depression or from all the pot.”

“Oh.”

“This seems more like not the clinical kind, like he’s just really moody. Like maybe he thinks a lot about existentialism or something.”

“Oh. Okay.” She scooped up some yellow potato mush with a piece of bread. “So what’s your next move?”

But I was still thinking about depression. “Actually,” I said, “‘moody’ is the wrong word. Because it’s only one mood, and it’s more like an attitude. It’s like he’s always on the verge of solving some sort of complicated problem that his whole life depends on, and like he can only solve it by sitting at the bus stop and concentrating really hard.”

“On what?”

“I don’t know. Maybe that’s part of what interests me. Like, wouldn’t it be nice to care that much about figuring something out? Wouldn’t it be nice if something mattered like that?”

“Now you sound depressed.”

“That’s what Jimmy said.” Jimmy was my actual best friend, whom I had not yet told about the electric man. “Jimmy told me that I’m depressed underneath the surface and I don’t know it.”

“Do you think he’s right?”

I shrugged. “No. But if he’s right, then I still wouldn’t think so, so that doesn’t prove anything.”

“What’s his evidence?”

“Well, you know how last year I went on that photography kick, then stopped? When I told him it was because paying so much attention to shapes was hurting my brain, he said that was a depressed person’s logic.”

She shrugged. “Jimmy’s weird. I mean, he’s great, but.”

“I know.”

“Anyway. Arthur’s mom is depressed.”

“Oh.”

“She wants to divorce his stepdad, but she says she can’t afford to. But she has this really expensive lizard. She could just sell it.”

“What does Arthur think?”

“He doesn’t have any room for his own thoughts. It’s like he’s his mom’s therapist. She calls all the time. I mean all the time. And he can’t say no. He has this suspicion that she prostituted herself to pay for his bar mitzvah and so it’s like an unpayable debt.” She pushed her tray away. “Anyway, I don’t know why I brought this up. Look, I wanted to show you something.” She flashed a wicked smile, her “sex life” smile, pulled out her phone, opened up the browser, and held the screen out for me to see.

It turned out she had just purchased his-and-hers butt plugs over the Internet for herself and Arthur. From her

blush, her girlish excitement, I could tell that she had never tried a butt plug before. Somehow her excitement about the butt plug seemed connected to her frustration over Arthur’s mom’s lizard. They were two sides of the same coin, or something.

I didn’t think about it too hard. I was busy acting excited for her benefit, which was easy because I actually did feel excited, for my own reasons. When I’d seen the butt plugs I’d been seized by an image: myself lying prone on the quilted surface of my bed, the golden man looming above me with a gleaming metal object in his hand.

The fantasy held power not because of any specific action the golden man might take next, but because of the feeling the scene contained: my total abjection before the daydream. Myself, limp-bodied yet taut with excitement. The daydream, erect and weaponized.

I barely heard anything Flor said after that. I had an idea for how to prolong the daydream without involving the golden man at all.

As I traveled around the library the next day, alphabetizing and straightening, I looked around to make sure no one was watching, and then I lingered in a section I had never explored before, one I had always disdained as the province of bored, gullible housewives. It contained titles like Kama Sutra for Dummies and Unlocking Your Inner Goddess and Touching the Lotus. I tripped my fingers along the spines and then pulled a book out at random.

It was called Animal Breathing for Women. I hid it under my desk all day and covertly checked it out before I went home. That evening I curled up with it in bed. Envision yourself as an animal, read the instructions for the first exercise. If you don’t intuitively know your spirit animal, consult a shaman or the Internet.

One of the great misunderstandings of our culture is its insistence that sex should equal fun. In the animal world sex is usually not fun, at least for the female. With ducks, for example, all sex is rape. In order to come to terms with this truth we must come to terms with our animal self.

The Regrets

The Regrets